Here’s a guest post, originally a Twitter thread, by Mareike Ohlberg of the German Marshall Fund. It’s a must-read for anyone who has ever cited, or seen a citation to, Chinese social media as an indicator of Chinese public sentiment about anything. The problems go way beyond the standard one of postings not being from a random sample of the public.

* * * * *

Given that much of the “Xinjiang cotton” backlash against multinational corporations that have expressed concern about forced labor takes place on social media, it is important to understand how much that space is actually dominated by party-state agencies which have the ability to censor comments that question the narrative they want to promote and flood social media platforms with paid online comments.

China Digital Times has documented and preserved some comments critical of the “Support Xinjiang Cotton” campaign that were deleted by censors. Thanks to efforts like these and others, people are aware that what we see on Chinese social media is skewed by censorship. What remains less understood is the other side of this coin: paid online commentators that can start and sustain campaigns such as “Support Xinjiang Cotton.”

To be clear: I am not suggesting that everybody on the Chinese internet, or even a significant percentage of people, is critical of the Support Xinjiang Cotton campaign, nor am I saying that everybody posting their support for Xinjiang cotton is a paid troll. But only when we understand how vast the paid online commentator system actually is can we begin to understand how easy it is for party-state agencies to get such a campaign started and keep its momentum.

So to give people a better idea of the scope and numbers of paid online commenting, I want to use the example of the Public Security Bureau (PSB) in Tieling Municipality 铁岭市 in the province of Liaoning in Northeast China. The information provided below is based on a public procurement notice from 2020, posted on behalf of the Tieling PSB on Liaoning’s provincial public procurement website (the entry is archived here; you can access the attachment in .docx format here). Keep in mind that all the numbers cited below are for a single government agency in a fifth-tier city.

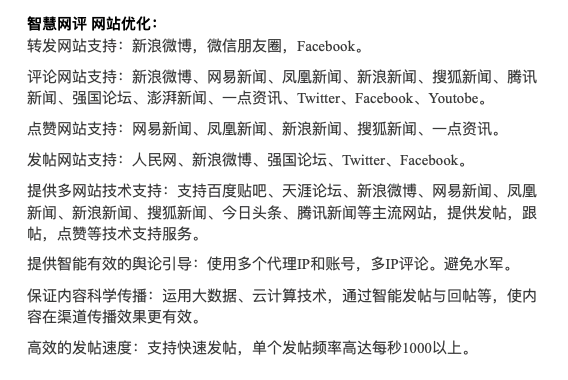

Figure 1 Above (Figure 1) is a section explaining the requirements for the upgrade of the PSB’s “intelligent online commenting” (智慧网评). Note that even a fifth-tier city PSB wants to post paid-for comments on Facebook, Twitter and Youtube alongside all the standard Chinese platforms such as Sina Weibo, WeChat Friend Circles, Baidu Tieba, and various news websites and aggregators. Also note that one of the upgrade requests is to be able to post 1000 comments per second. We don’t know if the system can actually do that, but that’s the request, and that’s a lot of comments for a single government agency in a relatively small city.

Above (Figure 1) is a section explaining the requirements for the upgrade of the PSB’s “intelligent online commenting” (智慧网评). Note that even a fifth-tier city PSB wants to post paid-for comments on Facebook, Twitter and Youtube alongside all the standard Chinese platforms such as Sina Weibo, WeChat Friend Circles, Baidu Tieba, and various news websites and aggregators. Also note that one of the upgrade requests is to be able to post 1000 comments per second. We don’t know if the system can actually do that, but that’s the request, and that’s a lot of comments for a single government agency in a relatively small city.

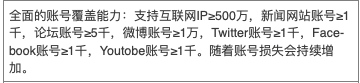

So what else does the Tieling Public Security Bureau want? For starters, a pool of 5 million IP addresses to post from. It also wants over 10.000 accounts on Weibo, and over 1000 on Facebook, Twitter and Youtube respectively, among other things (see Figure 2). Again, that’s a lot given who this request comes from.

Figure 2 A large part of the idea of smart commenting is automating certain tasks by providing templates and automating task dispatching and evaluation. Humans are still involved, but the idea is to be able to flood the space fast while reducing work load on individuals (see Figure 3).

A large part of the idea of smart commenting is automating certain tasks by providing templates and automating task dispatching and evaluation. Humans are still involved, but the idea is to be able to flood the space fast while reducing work load on individuals (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 There are other sections in the procurement document that talk about monitoring public opinion to detect any “negative public opinion” in time. Jessica Batke and I have analyzed similar monitoring systems in depth elsewhere. Since this particular public procurement document comes from a Public Security Bureau, it also mentions an additional system (referred to as “Wisdom Eye Inspection System” 慧眼落查系统) that is used to link virtual identities to phone numbers and IP addresses, as well as, presumably, to track people down in real life with this kind of information, as happened to Dr. Li Wenliang after he warned his colleagues privately about the new Coronavirus.

There are other sections in the procurement document that talk about monitoring public opinion to detect any “negative public opinion” in time. Jessica Batke and I have analyzed similar monitoring systems in depth elsewhere. Since this particular public procurement document comes from a Public Security Bureau, it also mentions an additional system (referred to as “Wisdom Eye Inspection System” 慧眼落查系统) that is used to link virtual identities to phone numbers and IP addresses, as well as, presumably, to track people down in real life with this kind of information, as happened to Dr. Li Wenliang after he warned his colleagues privately about the new Coronavirus.

This system for linking up identities actually requires a separate post to unpack what we know and don’t know about it, but it serves as a reminder that Chinese people and those based in China who post comments that are seen as sufficiently subversive do face real risks other than simply having their comments deleted and their accounts blocked.