Ling Li | In this essay, I point out that the age-limit norm is misrepresented and misperceived in current analyses of leadership changes in the Chinese Communist Party for two reasons. First, the method employed in these analyses fails to capture the complexity of the rules that constitute the norm. Second, the method is ill-equipped to reflect the stratification of power at the top of the Party. To rectify these issues, I provide a structured framework to examine the age distribution patterns of membership changes at national Party congresses. I conclude that the age-limit norm functions as a nondemocratic mechanism for the Party and its top leaders to facilitate the exit of current powerholders and redistribute power en masse in a peaceful manner with reduced cost, enhanced transparency, and reasonable credibility. The framework I offer can help reveal the hidden significance and resilience of the age-limit norm, which ha thus far been overlooked, obscured or underestimated in current analyses.

Citation:

Ling Li (2022) The Hidden Significance and Resilience of the Age-Limit Norm of the Chinese Communist Party, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 20, Issue 19, November 1. https://apjjf.org/Home

Keywords: Chinese Communist Party; Succession; Party Election; Party Congress; Age Limit

The age-limit norm is a vital instrument of self-governance of the Chinese Communist Party (hereafter referred to as ‘the Party’). Yet, it is also an elusive one. It is not in the Party charter—also known as the Party Constitution—nor does it appear in Party directives, regulations, or any other normative documents. Despite its elusiveness, its existence is widely acknowledged among analysts and observers. The rule of ‘seven up and eight down’—that is, 67 as a qualifying and 68 as a disqualifying age for Politburo membership—which many believe is the essence of the norm, has been used to predict leadership reshuffles within the Party for two decades. However, there has been no attempt to define the norm, to articulate its functions and features, or, least of all, to conceptualize it at an abstract level beyond its immediate empirical manifestations. This knowledge gap is striking and consequential given the importance of the topic. Without a clear understanding of what the norm entails and how it functions, misrepresentations and misunderstandings are inevitable.

In this study, I examine historical patterns of age distribution in membership changes in the top Party decision-making bodies and offer an analytical framework that can best capture these patterns. Based on my findings, I conclude that the primary function of the age limit is to facilitate and regulate the exit of top Party leaders. Only in the second order does it function as a selection criterion for membership renewal or new admissions. I also argue that when performing its second function, the age-limit rule is differentiated to reflect the different levels of prerogative enjoyed by different candidates. My findings show that, contrary to the nearly unanimous conclusion that the norm was dismantled by President Xi Jinping at the Twentieth Congress of the Party in October 2022, it in fact remains resilient. I further argue that a common flaw shared in current analyses that led to the above conclusion is the failure to recognize and/or take into account the layered power structure at the top of the Party and the staggered nature of the electoral process.

In the last parts of the essay, I substantiate my claim that the age-limit norm is significant for the self-governance of the Party in two respects. First, I situate the norm in a historical context and explain how it has outperformed previous mechanisms to redistribute power and how it does so with reduced cost, enhanced transparency, and reasonable credibility. I then compare it with alternative mechanisms, such as term limits or fixed retirement age, and explain what the age-limit norm brings to the continued rule of the Party that other mechanisms cannot.

Common Misunderstandings

During national Party elections, the most important seats to be filled are those on the top decision-making bodies that together constitute the ‘Party Center’.[1] The power structure of the Party Center has multiple, strictly hierarchical tiers. What complicates the issue is the fact that the higher tiers are also embedded in lower tiers, which gives them a false impression of equality.

At the operational level, the Party Center comprises four tiers[2] of stacked components: the office of General Party-Secretary (GPS), the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC), the Politburo, the Central Secretariat (CS),[3] and the Central Committee—each stacked on top of the next. Anyone with a seat on a higher body necessarily also occupies a seat on the lower ones. For instance, an elected PSC member is first elected as a member of the Central Committee and then of the Politburo. This also means that the membership composition of any tier is heterogeneous, consisting of both ordinary members and privileged members who also have seats on a higher body. Due to their higher ranking, privileged members are endowed with prerogatives that are not accorded to ordinary members. Such prerogatives structure the electoral process and its outcomes through the imposition of different levels of restriction on competition for seats at different ranks, which are reflected in candidate nomination criteria.

Party elections are staggered, which further complicates the issue. According to current electoral practices, a new member can be introduced only when there is a vacancy. However, the pace of the staggering is not fixed or predetermined but contingent on other factors. This feature has effectively bifurcated the electoral process: step 1 decides who among the sitting members should leave and who can stay; and step 2 decides who from the lower body will be promoted to fill any available vacancies. Each step involves a different group of candidates with different ranks and prerogatives, who are subject to different nomination criteria—a distinction that is easily overlooked if they are treated as a single group.

Current discussions tend to treat all seats on the Politburo as a single block, subject to one criterion, despite the body’s multitiered structure. What is also missing is a clear framework that take the staggered and bifurcated electoral processes into account. As a result, sitting members who have served at least one term at a given tier are treated the same as the new recruits lifted from a lower tier. This conflation can easily lead to a misreading of practices.

A Structured Framework

In this essay, I propose a structured framework to discuss the age-limit norm. This framework is designed to reflect the ranking differences between different categories of seats that constitute the Party Center, as well as those between sitting members and new members of the same decision-making body due to the bifurcated electoral process.

Under this framework, I divide leadership reshuffles at each tier into six types of events:

- Departure 1: Termination of membership of any given tier (Tier X) after exceeding the maximal age.

- Departure 2: Termination of membership of Tier X due to disciplinary measures or death.

- Departure 3: Termination of membership of Tier X without exceeding the maximal age.

- Renewal: Renewal of membership of Tier X.

- Promotion 1: A sitting member of Tier X is promoted to a higher tier.

- Promotion 2: A member from a lower tier is promoted to Tier X.

I then analyze the age[4] distribution patterns for four groups of leaders at the Party Center separately:

Group 1: Head of the Party

Group 2: PSC

Group 3: Politburo and the CS

Group 4: Central Committee (full members).

My dataset covers the period 1997–2022. Data included for analysis for each tier involve all members with an ordinary seat before the election and newcomers who are promoted to that tier at the election. Privileged members are analyzed at the highest tier at which they hold a seat. To demonstrate the differentiation in ranks, the event data for Promotion 1 of a given tier are also included in the event data for Promotion 2 of the higher tier.

Head of the Party

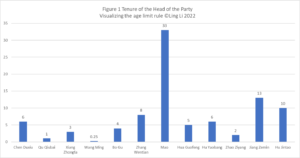

Since the head of the Party is only one seat, if I limited my analysis to the period 1997–2022, the sample would be very small. To make up for this limitation, I stretched the observation period and compared the tenure of each head of the Party through the entire history of the Chinese Communist Party, which shows no consistent pattern.

As Figure 1 shows, the length of tenure varies from three months to 33 years. From the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 until Xi came to power in 2012, there were six Party leaders. One (Mao Zedong) held the position for life; three were purged (Hua Guofeng, Hu Yaobang, and Zhao Ziyang), and two retired voluntarily. The age of retirement of the last two also shows no consistent pattern: Jiang Zemin retired at the age of 76, Hu Jintao at 69, and Xi, aged 69, just renewed for a third term.

Therefore, for the head of the Party, there is no consistent pattern of tenure or identifiable age regulating their exit.

[ To see the figures with better resolution, click and visit Asia-Pacific Journal, which provides full and free access to this essay in its entirety.]

Politburo Standing Committee

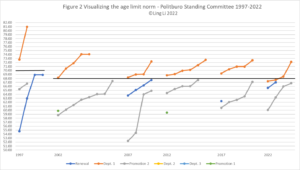

The PSC is the highest-ranking decision-making body at the Party Center; there is no higher collective body to which a PSC member can be promoted, except as head of the Party.

Figure 2 shows that all sitting PSC members at or over the age of 70 at the Fifteenth Congress in 1997 and 68 at subsequent congresses retired (Departure 1). The exit age of 68 was consistently observed at the Twentieth Congress, where both Li Zhanshu (72), a close associate of President Xi, and Han Zheng (68) retired. No sitting PSC member has been purged while in power during the period studied, so there are no data for Departure 2.

Between 1997 and 2017, all sitting PSC members aged under 68 successfully renewed their membership; hence, there are no data for Departure 3. This suggests that PSC members were given the prerogative to renew their membership automatically, barring those cases in which they had reached the age limit.

The pattern was, however, disrupted at the Twentieth Congress due to the premature departure of Li Keqiang and Wang Yang. Both were aged under 68 and neither was accused of any disciplinary violation, yet both failed to renew for another term.

This jarring violation is somewhat mitigated in an official account of the electoral process issued by the Party, which attributed their retirement to self-sacrificing voluntary abdication to make way for younger leaders (Xinhua 2022). This narrative is the same as that used to characterize the retirements of Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin.

Regardless of whether Li and Wang were compelled to ‘retire’ or left of their own volition, this Party-issued narrative helps to maintain the prerogative of PSC members to stay in power until they reach the age limit. If one decides to abdicate their prerogative and step down before reaching the age limit, that is an individual choice. We will have to wait to see whether the cases of Li and Wang will have an impact on future practices.

Regarding Promotion 1, two PSC members were promoted to head of the Party during the study period: Hu Jintao in 2002 and Xi Jinping in 2012. Both were 59 when promoted. Regarding Promotion 2, Figure 2 shows no-one aged over 70 in 1997 or aged over 68 since has been promoted from a lower body to the PSC. This rule was consistently observed at the Twentieth Congress.

Politburo and the Central Secretariat

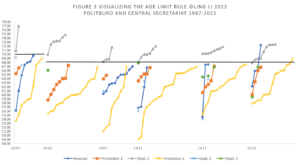

Figure 3 shows that the age limit—70 in 1997 and thereafter 68—that has facilitated the departure of sitting PSC members is also valid for Politburo and CS members (Departure 1, grey line). All sitting members above the age limit retired peacefully at the election. However, for this group of Party leaders, age is not the necessary condition for retirement; during this period, six sitting members under the age limit were expelled from the Politburo and CS under disciplinary measures.

In addition, Figure 3 shows that a sitting member can be pushed out before reaching the age limit without a disciplinary cause. This practice started in 2002 at the Sixteenth Congress overseen by Jiang Zemin, where Li Tieying, at the age of 66, failed to renew his Politburo membership. At the Eighteenth Congress overseen by Hu Jintao, Wang Lequan, another age-eligible (67) Politburo member, was denied renewal of his membership. In 2017, Xi Jinping expanded the practice by retiring three age-eligible Politburo members at the Nineteenth Party Congress. At the Twentieth Congress, two age-eligible members departed without cause: Hu Chunhua (59) and Chen Quanguo (67). Hu’s early departure was unexpected but does not count as a violation of the norm.[5]

These observations suggest that between 1997 and 2017, reaching the age limit was only a sufficient but not a necessary condition for a Politburo and CS member to retire, unlike PSC members, for whom it was both a sufficient and a necessary condition to retire. It follows that being under the age limit is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a Politburo and CS member to stay or be promoted to the PSC, or for a member from the lower tier to be promoted to the Politburo and CS.

This rule was, however, broken twice at the Twentieth Congress: military leader Zhang Youxia was re-elected to the Politburo at the age of 72; and Wang Yi, currently Minister of Foreign Affairs, was promoted to the Politburo from the Central Committee at age 68, passing the age limit.

These violations show that the binding force of the age-limit norm has been softened by the introduction of exceptions. The criteria for such exceptions have not been revealed, but it is reasonable to assume, given the nature of the offices held by Zhang and Wang, that they were justified by the heightened concerns about ‘homeland security’ repeatedly emphasized by President Xi in his report to the congress.

Other than these two cases, the age-limit rule was observed, which shows that violations are exceptional, localized, and deliberate rather than the norm.

Central Committee

The Central Committee is nearly 10 times larger than the Politburo. Compiling a historical dataset of the ages of all its members, past and present, is beyond the resources of this study. Perhaps due to this practical challenge, our understanding of the age-limit norm is fuzziest at this level. There is no conclusive evidence that Central Committee membership is regulated by the same age limit (68) as the Politburo, the CS, and the PSC, or by a lower threshold—for instance, 65, which is the official retirement age for ministerial-rank officials, from whom the Central Committee’s full members are selected.

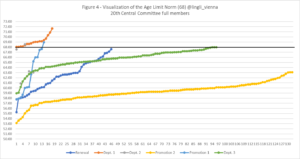

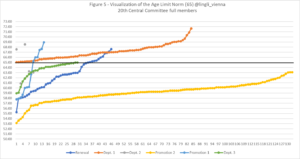

In this study, I compiled an age dataset of all full members of the nineteenth and twentieth congresses. Next, I applied both age limits, 68 and 65, to examine how they affected membership changes on the Central Committee.

Figure 4 shows the result when age 68 is applied, indicating this is the trigger for departure for all sitting members above the age limit (Departure 1, orange line) with one exception: Wang Yi, as explained. Apart from Wang, 68 also holds as the maximal age for a sitting member to renew membership (Departure 3, blue line) or receive a promotion (Promotion 1, light-blue line). At the Twentieth Congress, 46 sitting Central Committee members had their membership renewed and 14 received a promotion—all of whom were under 68 years of age.

The admission of new members from the lower body, however, seems to follow a much lower age limit. Among 132 new members (not counting two who were directly lifted to the Politburo) who were promoted from subnational positions at the Twentieth Congress (Promotion 2, yellow line), none had reached 64 at the time of the election.

Figure 4 shows clearly that the age limit is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a sitting Central Committee member to renew their membership or receive a promotion. Among 160 sitting Central Committee members who were aged under 68, only 46 (29 per cent) stayed, 14 (9 per cent) were promoted, 96 (60 per cent) departed peacefully, and four (3 per cent) left because of disciplinary measures or death. In addition, the rate of ejection is much higher on the Central Committee (96/160, 60 per cent) than on the Politburo and CS (2/9, 22 per cent). This is because the lower one goes on the rank ladder, the fewer prerogatives their members enjoy and the higher are their rates of ejection.

Figure 5 shows that when we apply 65 as the age limit, the patterns of membership changes significantly weaken. Unlike the patterns shown in Figure 4, when 65 is applied, the age factor can no longer explain the renewal or promotion of a significant number of members who are above the age limit.

Therefore, it appears that Central Committee members are subject not to the age limit of 65, as many believe, but to 68, as are members of the Politburo and above, at least at the Twentieth Congress.

Historical Significance

My findings show that the age-limit norm has not been dismantled under Xi’s rule. Rather, its existence can be tracked and the rule is very much alive and potent. The disruption we witnessed at the Twentieth Congress was not a revocation but rather a modification of the norm. As with any emergent norm, it can evolve over time.

As shown in my analysis, the age-limit norm is not one-size-fits-all. Even though it uses the same age threshold—currently 68—as the trigger for membership changes at different tiers of the decision-making bodies of the Party Center, its application differs from tier to tier. For lower-tier bodies, the age limit is a sufficient but not necessary condition to trigger departure and a necessary but not sufficient condition to grant membership renewal or promotion.

For top-rank Party leaders sitting on the PSC, the age-limit norm has been both the necessary and the sufficient condition to trigger their exit since 1992. This is significant because, before the emergence of the norm, PSC members could be removed only through disciplinary measures powered by political campaigns. The difficulty of removing top-ranking Party leaders is the direct outcome of the self-rule of the PSC; unlike all other Party decision-making bodies, whose membership is filled by those of their superior decision-making body, the PSC has been sitting at the apex of power since the Party gained autonomy from the Soviet Communist Party decades ago.

It is hardly surprising that the self-governing PSC used to grant its members life tenure. The advantage of life tenure, from the Party’s point of view, is that it provides PSC members with security and helps to stabilize factional politics. However, it also creates a gerontocracy.

Starting in 1982, when the average age of PSC members had reached 74.5, the Party began experimenting with schemes to persuade members to retire. One such scheme was the creation of the Central Advisory Committee (CAC), which removed the first-generation Party elders from day-to-day administration but allowed them to continue to participate in decision-making from the back seat. However, backseat drivers can sometimes be just as disruptive. In 1992, the CAC was abolished and it was during this period that the age-limit norm emerged.

Functional Significance

Since the abolition of the CAC, the age-limit norm has been adopted as an alternative, nondemocratic mechanism to regulate the exit of members of the top Party decision-making bodies en masse in a peaceful manner. It functions as a metabolizing mechanism to rejuvenate the Party’s elite core. The age-based norm is simple, objective, stable, predictable, and easy to enforce, while also providing space for differential treatment to honor different levels of prerogatives preserved for different groups of leaders.

Yet, to facilitate a deeper understanding of the significance of the age-limit norm, we can turn to two pertinent questions that have never been asked, let alone answered: Why did the Party not adopt other mechanisms to facilitate the exit of top-ranking leaders, such as a term limit or fixed retirement age? What can the age-limit norm bring that the other mechanisms cannot?

Both term limits and fixed retirement ages are widely adopted in personnel management in China; age-limit is an additional tool with distinctive functions.

Compared with the age limit, erm limits are not a suitable mechanism to regulate the exit of top-ranking Party leaders. First, in China, there is no professional segregation between career politicians (leaders holding executive positions in Party or state institutions) and civil servants. Career politicians are part of the civil service and are managed as civil servants. This means their tenure is not attached to electoral terms and their service does not end when their term of office ends.

Term limits trigger only job rotation, not termination of service. When a term limit has been reached, what usually follows is rotation to a different position of equal ranking. This is because one of the goals of the Party’s personnel system is to prevent a monopoly of power by individuals’ prolonged occupation of an office. The system is, however, also concerned about the retention of reliable service from its political elite and the cooption of this group. Term limits can deliver only the first goal. The age-limit norm helps to deliver others because it allows top-ranking Party leaders to retain their membership of top decision-making bodies and stay in power beyond their term limit and before they reach a senior age, which helps the Party to stabilize its metabolism, as it were, and to regulate the pace of membership replacement.

The age-limit norm also achieves what the introduction of a fixed retirement age cannot. First, the norm allows continuity of governance and avoids disruption amid an electoral term as would happen with a fixed retirement age. Therefore, the retirement age practice is limited to lower positions and does not apply to central Party leaders. Second, unlike a retirement age, which triggers one’s exit the moment the age is reached, the age-limit norm triggers one’s exit only at the end of a term, thus permitting a delay of retirement, depending on one’s age in relation to the electoral cycle, for a maximum of five years (to age 73). Third, a fixed retirement age implies an entitlement to employment until that age limit is reached, while the age-limit norm, when applied below the PSC, serves only as an eligibility criterion. It opens the process to an array of hidden factors, thus permitting considerable room for discretion or arbitrariness in the hands of those who make the selections.

Conclusion

Based on the historical patterns demonstrated in this essay, I conclude that the age-limit norm functions as a nondemocratic mechanism for the Party and its top leader to facilitate the exit of current powerholders and subsequently redistribute power en masse in a peaceful manner. I contend that the age-limit norm is indispensable for the Party’s continued rule. Its value lies not only in its historical but also in its functional significance. It has outperformed any of the previous mechanisms used to redistribute power and it does so with reduced cost, enhanced transparency, and reasonable credibility. Compared with alternative mechanisms, such as term limits and a fixed retirement age, it allows the Party to retain prolonged—but within regulatory limits—service from its most trusted elite and reward them with longer tenure and associated privileges. In addition, by adjusting the exclusivity of the age factor as a candidate selection criterion, the age-limit norm permits, despite its enhanced transparency, considerable discretion in the hands of those who oversee the electoral process.

I further argue that current analyses of the age-limit norm have compressed a multitier structure and multidimensional process into something of one size that is supposed to fit all. This oversimplification fails to capture the complexity of the rules that regulate Party leadership reshuffles or reflect the stratification of power at the Party Center. Every so often, observers claim that rules are broken when there are none and fail to recognize them when they are present. As a result, observers’ perceptions of the scope of application of the age-limit norm become unduly narrow and its significance and durability are underestimated.

Author’s Bio: Ling Li teaches Chinese Studies at the University of Vienna. She obtained her doctoral degree of law from Leiden University. Before coming to Vienna, she was a Senior Research Fellow at the US–Asia Law Institute of the New York University School of Law, where she remains a non-resident fellow. Her main research field is Chinese law and politics, with a particular focus on the structural features of the Party-State and the institutional practices of the Chinese Communist Party. She has also published extensively on corruption, anticorruption, and the operation of courts in China. She is currently writing a book titled Corruption, Law and Power Struggles: The China Model, which will be published by Cambridge University Press in 2023.

References

Li, Ling. 2022. ‘Cover Story: How China’s Party Congress Actually Works.’ The Diplomat, 1 September.

Xinhua. 2022. ‘领航新时代新征程新辉煌的坚强领导集体——党的新一届中央领导机构产生纪实 [New Era, New Journey, and New Glory under a New Collective Leadership: A Documented Account of the Birth of the New Central Leadership of the Party].’ 新华社 [Xinhua], 24 October. www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-10/24/content_5721222.htm.

[1] ‘Elections’ within the Party are fundamentally different from those that take place in other political systems. Others may prefer to call this process ‘selection’, but for the sake of simplicity I use ‘election’ throughout the essay with full knowledge of its distinctive features. For a brief discussion of the characteristics of this process, see Li (2022).

[2] Other than these four components, the Party Center also includes the Central Military Commission and the Central Commission of Discipline and Inspection. For simplicity, the latter two are not discussed here because their functions and mandates are limited to specialized fields.

[3] Between the Central Committee and the Politburo, there is also the Central Secretariat, which sits above the Central Committee and is mandated to operationalize the decisions of the Politburo and the PSC. Because most members of the Central Secretariat also have seats on the Politburo, the two are conflated in my statistical analyses.

[4] For the dataset of all figures, a member’s age is calculated on the first day of the month when the election is held. For a few members of the lower tiers of decision-making bodies, information about their date of birth is incomplete. In such instances, the fifteenth day of their disclosed month of birth is assigned as the presumptive birthdate.

[5] Before the congress, Hu was the youngest but the most senior in terms of the number of years served as a sitting Politburo member and was considered a strong contender for a seat on the PSC.