I’ve been looking through a recent massive collection of Chinese court statistics going from 1949 to 2016 (人民法院司法统计历史典籍) (“People’s Court Historical Statistics” or “PCHS”) and will be posting from time to time on interesting finds. [MAY 20, 2020 UPDATE: The Dui Hua Foundation has a blog post about this series from last November here. They are also periodically posting their findings.] This post will be about acquittal rates, because the statistics show something interesting and counterintuitive: that acquittal rates were higher in the Mao era than in the post-Mao era, and have been historically and extremely low in the last several years.

First, some general remarks on acquittal rates. Acquittal rates in China have always been low—under 0.2% every year from 2006 to 2016—but the question is what conclusions one can draw from that.

Without information on what kinds of cases are brought to trial—information that only in-depth fieldwork would reveal—it’s hard to know what to make of acquittal rates. It is theoretically possible that doubtful cases are never brought to trial, although well-publicized cases of miscarriages of justice make that hypothesis a bit implausible. But just how implausible is impossible to say.

The acquittal rate in the United States is much higher: in federal courts, a recent study found that the average conviction rate in jury cases was 84%, while judges convicted slightly more than 50% of the time; a quick Google search finds estimates of the overall acquittal rate ranging from 17% to about 25%. (I have not researched this extensively and would welcome better numbers.)

A Caixin report on acquittal rates from 2016 (link now dead) cites figures for other countries, including 2% in Finland, 9% in the US, and a whopping 25% in Russia.

East Asian countries have much lower acquittal rates. Consider this report on South Korea:

Prosecutors normally indicted only when they accumulated what they considered overwhelming evidence of a suspect’s guilt. The courts, historically, were predisposed to accept the allegations of fact in an indictment. This predisposition was reflected in both the low acquittal rate–less than 0.5 percent–in criminal cases and in the frequent verbatim repetition of the indictment as the judgment. The principle of “innocent until proven guilty” applied in practice much more to the pre-indictment investigation than to the actual trial.

The acquittal rate in Japan is less than 1 percent. (For a good study of the Japanese criminal prosecution system, see David Johnson, The Japanese Way of Justice: Prosecuting Crime in Japan (2002), reviewed here.)

Interestingly, Taiwan’s acquittal rate is 12%—lower than the US but still in the same ballpark, while conspicuously higher than that of Japan or South Korea, to whose criminal justice systems its own bears a much higher formal resemblance. [MAY 5, 2020 ADDITION: I shouldn’t have said Taiwan’s rate was lower than the US, since my numbers for the US are all over the place and not very reliable. See also the discussion of the significance (or lack thereof) of US acquittal rates here.] Another source reports a somewhat lower rate:

According to statistics released by the Ministry of Justice, the proportion of those released without prosecution is about 20 percent yearly. The conviction rate of those that go to trial is more than 90 percent.

What, then, can we conclude with a reasonable degree of certainty from low acquittal rates?

- Guilt is obviously not really being determined in any serious way at the trial stage—in fact, trial is really a misnomer. This doesn’t necessarily mean that a system with low acquittal rates railroads all suspects; it could be that it makes an efficient and good-faith determination of guilt before the stage labeled “trial” so that the non-guilty never get that far. But what a low acquittal rate does tell us is that it doesn’t do any good to give suspects a lawyer, even the best one in the world, for their trial. A criminal procedure system that makes the decision on guilt before the trial must, to be fair, give suspects full rights to a defense at the critical pre-trial stage. In the case of China, of course, this is not what happens.

- A high acquittal rate, such as we see in Russia (if it’s really that high) would be evidence that judges and prosecutors/police aren’t in bed together. A low acquittal rate is not evidence that they are, since again it could be that prosecutors are really, really careful, but it’s consistent with that hypothesis.

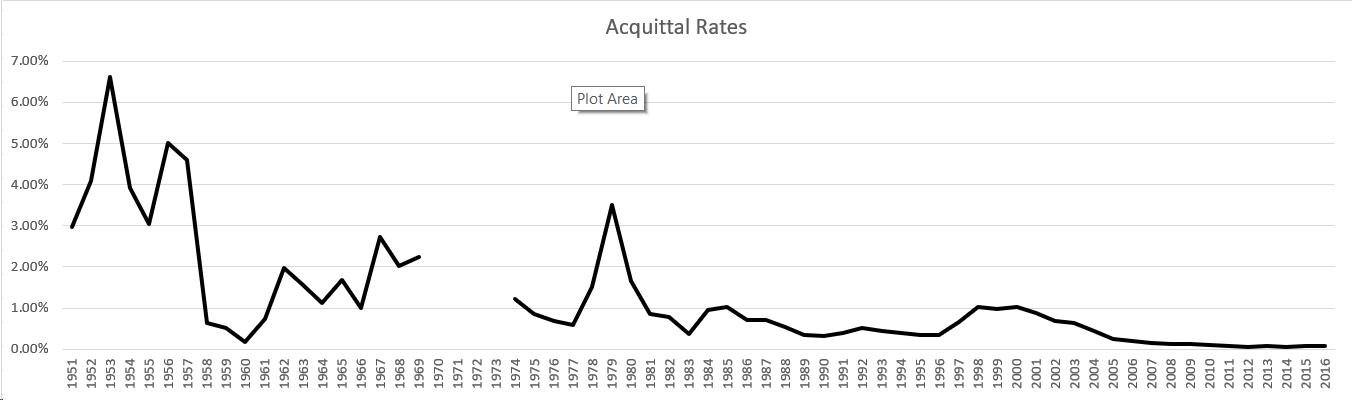

Now for the Chinese numbers in detail. Here’s a graph showing acquittal rates from 1951 to 2016. (Underlying data from PCHS is at the end of this post.)

What immediately jumps out, of course, is the relatively high rates of acquittal in the 1950s (almost 7% in 1953) and the extraordinarily low rates in the last several years (only 6 in 10,000 in 2012). The sharp drop in 1958, already begun in 1957, is pretty clearly an effect of the Anti-Rightist Campaign. But the rate creeps back up, and right up into the Cultural Revolution stays many multiples of today’s microscopic rates. There is one dip to 0.18% in 1960, but other than the acquittal rate is below 0.2% only after 2005, and it stays down there for every year (0.09% in 2016).

Thus, it seems that there was much less coordination between the courts on the one hand and prosecutors and police on the other during the Mao era than there is today. Again, this doesn’t necessarily mean that there was more justice in the Mao era than today; today’s results could be (although I don’t think are) explained by imagining sturdily independent courts that refuse to convict except where the evidence is absolutely overwhelming, and thus deter prosecutors from bringing any other kind of case. On the other hand, the statistics do suggest that courts up until the Anti-Rightist Campaign were more able to push back against police and prosecutors than we (OK, maybe just I) thought. And finally, they show that whatever the cause, today’s acquittal rate is extraordinarily low and aberrational not just by international standards, but by historical standards in the PRC as well.

Here is the specific data:

| Criminal judgments (persons) | Acquittals (persons) | Percentage | |

| 1950 | 169,847 | ||

| 1951 | 134,011 | 3,993 | 2.98% |

| 1952 | 661,789 | 27,024 | 4.08% |

| 1953 | 675,476 | 44,651 | 6.61% |

| 1954 | 805,279 | 31,660 | 3.93% |

| 1955 | 965,828 | 29,491 | 3.05% |

| 1956 | 473,042 | 23,664 | 5.00% |

| 1957 | 552,782 | 25,421 | 4.60% |

| 1958 | 1,682,446 | 10,721 | 0.64% |

| 1959 | 532,772 | 2,815 | 0.53% |

| 1960 | 500,727 | 921 | 0.18% |

| 1961 | 460,052 | 3,404 | 0.74% |

| 1962 | 291,190 | 5,738 | 1.97% |

| 1963 | 335,477 | 5,202 | 1.55% |

| 1964 | 131,217 | 1,467 | 1.12% |

| 1965 | 118,279 | 1,977 | 1.67% |

| 1966 | 154,233 | 1,543 | 1.00% |

| 1967 | 54,978 | 1,496 | 2.72% |

| 1968 | 71,229 | 1,436 | 2.02% |

| 1969 | 87,502 | 1,964 | 2.24% |

| 1970 | 304,798 | 0.00% | |

| 1971 | 206,867 | 0.00% | |

| 1972 | 183,012 | 0.00% | |

| 1973 | 142,035 | 0.00% | |

| 1974 | 118,770 | 1,452 | 1.22% |

| 1975 | 148,220 | 1,254 | 0.85% |

| 1976 | 147,970 | 1,003 | 0.68% |

| 1977 | 210,464 | 1,231 | 0.58% |

| 1978 | 144,304 | 2,197 | 1.52% |

| 1979 | 140,108 | 4,925 | 3.52% |

| 1980 | 197,143 | 3,282 | 1.66% |

| 1981 | 258,457 | 2,238 | 0.87% |

| 1982 | 275,223 | 2,129 | 0.77% |

| 1983 | 657,257 | 2,470 | 0.38% |

| 1984 | 600,761 | 5,764 | 0.96% |

| 1985 | 277,591 | 2,826 | 1.02% |

| 1986 | 325,505 | 2,321 | 0.71% |

| 1987 | 326,374 | 2,350 | 0.72% |

| 1988 | 368,790 | 2,039 | 0.55% |

| 1989 | 462,853 | 1,582 | 0.34% |

| 1990 | 582,184 | 1,912 | 0.33% |

| 1991 | 509,224 | 1,983 | 0.39% |

| 1992 | 495,364 | 2,547 | 0.51% |

| 1993 | 451,920 | 2,000 | 0.44% |

| 1994 | 547,435 | 2,153 | 0.39% |

| 1995 | 545,162 | 1,886 | 0.35% |

| 1996 | 667,837 | 2,281 | 0.34% |

| 1997 | 529,779 | 3,476 | 0.66% |

| 1998 | 533,790 | 5,494 | 1.03% |

| 1999 | 608,259 | 5,878 | 0.97% |

| 2000 | 646,431 | 6,617 | 1.02% |

| 2001 | 751,146 | 6,597 | 0.88% |

| 2002 | 707,036 | 4,938 | 0.70% |

| 2003 | 747,096 | 4,835 | 0.65% |

| 2004 | 767,951 | 3,365 | 0.44% |

| 2005 | 844,717 | 2,162 | 0.26% |

| 2006 | 890,755 | 1,713 | 0.19% |

| 2007 | 933,156 | 1,417 | 0.15% |

| 2008 | 1,008,677 | 1,373 | 0.14% |

| 2009 | 997,872 | 1,206 | 0.12% |

| 2010 | 1,007,419 | 999 | 0.10% |

| 2011 | 1,051,638 | 891 | 0.08% |

| 2012 | 1,174,133 | 727 | 0.06% |

| 2013 | 1,158,609 | 825 | 0.07% |

| 2014 | 1,184,562 | 778 | 0.07% |

| 2015 | 1,232,695 | 1,039 | 0.08% |

| 2016 | 1,220,645 | 1,076 | 0.09% |

We have a real shot at acquittal or conviction on lesser charges in a jury trial in the USA. But the reality is that few go to trial. Draconian sentencing makes only a few willing to risk trial. See New York federal judge Jed Rakoff’s discussion:

https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1292&context=nulr

Rakoff: “by 2000 only 5% of all federal defendants (reportedly

even a smaller percentage of state defendants) went to trial. In 2015, only

2.9% of federal defendants went to trial, and, although the state statistics

are still being gathered, it may be as low as less than 2%.”

And sentences even after the guilty pleas are much longer in the U.S.

We have 25% of the world’s prisoners, 5% of the population.

This is not a defense of the Chinese prosecutors, just broadening the reference points.

5% of what? People arrested or people convicted? The latter is a statement only about plea bargaining, which is a different subject.

“A Caixin report on acquittal rates from 2016 (link now dead) cites figures for other countries, including 2% in Finland, 9% in the US…”

“Interestingly, Taiwan’s acquittal rate is 12%—lower than the US but still in the same ballpark”

So Taiwan’s acquittal rate is actually higher than the US?

My original post was confusing. (I had pasted in language from two old blog posts, leading to an inconsistency.) I’ve fixed it. Thanks for the alert.