“Aha – I knew it! Told ya so.” That, in so many words, is the reaction from some people I’m seeing in social media, as well of course as in Chinese officialdom, to the November 18th report that Michael Spavor is seeking a multimillion dollar settlement from the government of Canada. (He has not, to the best of my knowledge, filed a lawsuit.) According to the report, he is “alleging he was detained because he unwittingly provided intelligence on North Korea to Canada and allied spy services. Michael Spavor alleges that the deception was conducted by fellow Canadian prisoner Michael Kovrig, and it was intelligence work by the latter that led to both men’s incarceration by Chinese authorities”. This report, or more precisely the allegation contained in the report, is being cited as proof (or at least probative evidence) that Michael Kovrig was a spy after all, that his detention was justified, and that all the doubters were just motivated by emotion, anti-China bias, or what have you.

I disagree. Everyone should just take a breath and read what the report actually says.

Let’s take a look at what conclusions were (before the report) and are now (after it) justified. What did we know before this report came out and what new light, if any, does it shed?

There are two competing explanations for the detention of the Two Michaels: (1) arbitrary hostage-taking in retaliation for Canada’s detention of Meng Wanzhou, and (2) genuine and justified suspicion by the Chinese authorities, later confirmed upon further investigation, that Spavor and Kovrig engaged in espionage in violation of China’s Criminal Law.

Evidence up to November 18th

What evidence was available at the time of the detentions (late December 2018) and since then all the way up to November 18th, and which explanation did that evidence suggest was more likely?

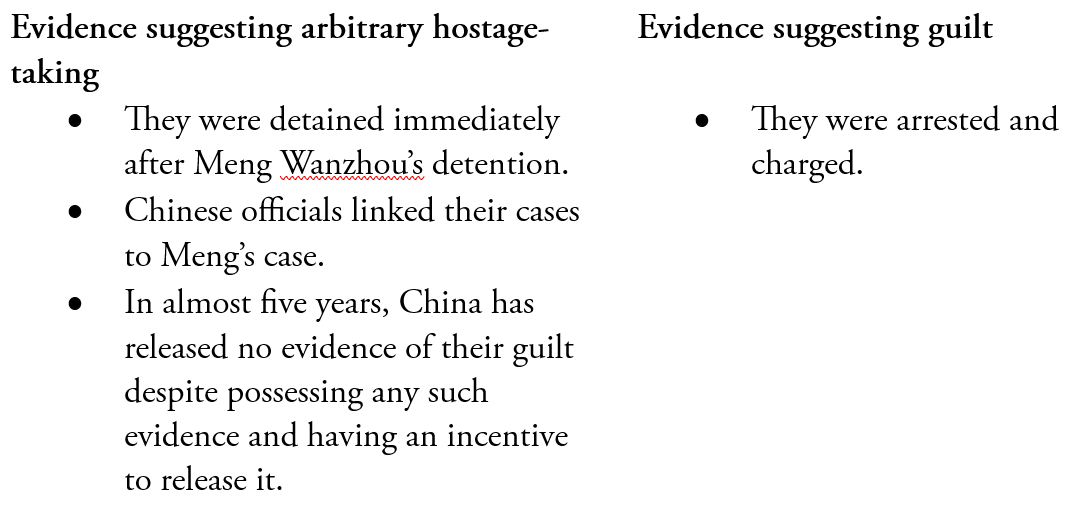

First, what was the evidence in favor of Explanation 2? Well, they were arrested and charged. Personally, I don’t find that reasoning (“The authorities wouldn’t have arrested them if they weren’t guilty”) terribly probative. Quite properly, it is not the reasoning that most people I know in China circles applied to the Gang Chen case, and I suspect that very few readers will apply it to the case of Evan Gershkovitz, the Wall Street Journal reporter detained in Russia on spying charges. As with Kovrig and Spavor, do we know for sure that Gershkovitz was not a spy? No. But we can also say that the mere fact of his arrest does not push the needle very far in favor of his guilt.

Anything else? Here’s the key point: there’s nothing else. The fact of their arrest has been the totality of the evidence, if we can call it that, against them. Moreover, let us not forget that incriminating evidence, if it exists, is in the hands of the Chinese government, yet in the almost five years since the detention of the Two Michaels, they have not revealed one iota of it. And they denied consular access to the trials, in clear violation of the Canada-China agreement on consular relations, so no outside observer has ever seen the evidence, if any.

And don’t talk to me about the need to protect sources and methods. In a genuine espionage case, that could certainly account for a government’s unwillingness to reveal some evidence. But it doesn’t account for China’s unwillingness to release any evidence. It’s no secret that Chinese security authorities can tap your phone or your residence; where are the transcripts of the secret conversations? It’s no secret that Chinese security authorities can follow you around and take photographs. Where are the photos of the clandestine meetings?

All right. What’s the evidence in favor of Explanation 1? First, of course, is the timing. If it was a genuine espionage case, that’s very hard to explain. Just coincidence? Second are the comments by various Chinese officials themselves linking the detentions to the Meng case. Third, there is the fact, noted above, that in almost five years, and despite it being in China’s interest to do so, China has not released a shred of even debatable and contested evidence of the Two Michaels’ guilt. One might even add a fourth item: that China was fine with releasing them once Meng was released. But I’m not even going to count that.

To sum up:

It’s very hard for me to understand how one could look at the evidence on both sides and conclude that it’s more likely than not that Explanation 2 is the correct one.

New evidence revealed by the Nov. 18th report

Now let’s ask what new evidence bearing on the likelihood of each explanation is revealed by the Nov. 18th report that Michael Spavor is seeking compensation from the Canadian government.

First, we have to remember that what we have is a press report from anonymous sources about allegations. We don’t know with certainty and specificity what Spavor has alleged. And of course not all allegations are accurate. Thus, to rely on one press story to say, “You see? I was right!” seems maybe a teeny bit premature.

But let’s assume for the sake of argument that the allegations have been reported correctly and are accurate. They amount to saying that Kovrig got information about North Korea from Spavor and passed that information on to the Canadian government. Where does that allegation state a violation of China’s Criminal Law?

I’m just not seeing how this report changes anything, and suddenly makes unsound any judgments about the plausibility of the two explanations that were reached before it came out.

Making judgments in the face of uncertainty

Let me finish with some thoughts on making judgments in the face of uncertainty.

- To say we should wait for certainty on some issue before passing judgment is not a neutral position. People need to make decisions (for example, “Is it risky for me to go to China?”) on the basis of imperfect information and uncertainty, and therefore the two critical questions are: (a) what we should take as the default position in the absence of certainty, and (b) how much certainty we should require before making a judgment, given that in many things, true certainty is impossible and we have to go by probabilities. The choice one makes on these questions needs to be justified. There is no natural, self-evident answer. Regarding the Two Michaels case, when the Chinese government after five years has still not released any evidence, to say, “Hey, let’s suspend judgment while we are still uncertain” is not a neutral, objective stance.

- If one’s judgment on any issue turns out to be wrong, the intellectually responsible thing to do is to go back and figure out why one’s judgment was wrong and what one can do so as not to be wrong next time. In other words, what was the problem with one’s decision-making procedure? The important point here is that turning out to be wrong is not per se proof that the decision-making procedure was wrong. If it turns out tomorrow that climate change really is a gigantic hoax perpetrated by a massive conspiracy of climate scientists, that does not mean I was wrong to believe such a conspiracy highly improbable and to rely, as a non-expert, on the consensus of climate scientists. We always have to be dealing in probabilities.

- On the question of the Two Michaels, I think we all have access to the same pool of information. To me, the information to which we all have access suggests a greater probability to the theory of retaliatory detention than to the theory of genuine espionage. As noted above, the only known fact I’ve ever heard adduced in favor of the genuine espionage theory is the fact that they were arrested and charged. Different people will assess the probative value of that undisputed fact differently, of course. But it’s hard for me to see how it outweighs the evidence in favor of the probability of the retaliatory detention theory. Thus, my claim is not that I know for sure what the truth is. It’s that I understand that sometimes we have to make judgments in the face of uncertainty, and waiting indefinitely for certainty is a choice with consequences that has to be justified and will invariably favor one side in a dispute.

Hello,

Further to the China Collection article, personally I don’t know anyone who doubts the “hostage” theory of the Two Michael story.

Nor do I know anyone who doubts that whatever charges were brought in the PRC courts were on facts and laws that would not have led to charges in our own countries.

So, those are not the interesting questions in this case.

What is interesting, and important, is whether the Canadian Government in one way or another mandated one or the other or both Michaels to do what the PRC accuses them of having done.

On the answer to that question could depend the need to answer others, such as if there was such a mandate, why not have admitted it earlier and gotten the Two Michaels home sooner?

This article avoids the excessive language used on the China Law List to discredit Michael Spavor and his eventual case.

But, it continues to push forward premature conclusions based largely on speculations, as the author himself recognized:

“First, we have to remember that what we have is a press report from anonymous sources about allegations. We don’t know with certainty and specificity what Spavor has alleged.”

Daniel Laprès

Avocat au Barreau de Paris

Barrister& Solicitor (Nova Scotia)

“personally I don’t know anyone who doubts the “hostage” theory of the Two Michael story.” Clearly we share different Twitter and Facebook feeds. If I hadn’t been seeing this doubt (in some cases from the beginning) I wouldn’t have bothered taking the time to write the post.

For the reasons explained in the post, I believe it is neither neutral nor objective after five years of waiting for evidence to say that drawing conclusions is “premature”. No conclusion is going to be certain. But waiting for certainty is not neutral or objective. We have to go with probabilities.

Finally, I don’t understand the claim that admitting the Two Michaels were spies (if they were) would have brought them home sooner. What China wanted, and what secured their release, was not a Canadian government admission about their guilt. It was the release of Meng. We don’t even know what the Canadian government might have admitted, since we don’t know what specifically the Chinese government charged the Two Michaels with doing that violated the Criminal Law. To the best of my knowledge no outsider has even seen the indictment, let alone the evidence.

Spavor’s allegation, as reported, is sloppy about the difference between espionage and the broader activity of gathering intelligence. If I am legally near the Chinese border with the DPRK, see something interesting, and tell it to Michael Kavor, I did not spy. That is the common understanding of these things; I suppose the Kafka-esque language of Chinese “law” might be different.