“Contrary to the popular assumption that the office of GPS is vested with boundless absolute power, the Directive has endowed no substantive power to it. The GPS has no veto power and no casting vote on any nationwide cross-sector policy issues discussed at any decision-making body at the Party Centre. Instead, the power to make such polices is divided between the CC, the Politburo and the PSC.”

___________________________________________

In Part I, I stressed the point that one should take Party rules seriously because breaking rules entails costs, even for people who make these rules. Another reason that we should take Party rules seriously is that rules matter when they are about the sharing or distribution of power among the powerful. When actors of more or less equal power are in dispute, their conduct will be subject to the similar level of scrutiny and the rules become an important criterion to assess the propriety of conduct. Therefore, rules on the constitution and operation of the highest decision-making body of the Party are particularly noteworthy. The Directive on the Operation of the Central Committee (the Directive) issued on September 30, 2020 is one such set of rules.

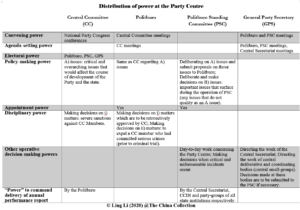

Next, I summarize the Directive by first dissecting the decision-making power into 7 types based on their utilities and then tabulating the allocation of these powers based on my reading of the Directive. Lastly, I provide the key takeaways on their implications.

Types of decision-making powers

Convening power: the power to decide when to call for a meeting.

Agenda setting power: power to select and decide what issues are subject to deliberation and/or voting at a collective decision-making meeting.

Electoral power: the power to elect a decision-making body and to determine rules on the election.

Policy-making power: power to deliberate and decide on policy issues.

Appointment power: power to recommend, make or approve personnel decisions regarding appointed posts.

Disciplinary power: power to investigate and sanction peers.

“Power” to command the delivery of a performance report: the non-consequential entitlement to command the submission of a performance report annually by a subordinating body.

Distribution of power at the Party Centre

Some quick takeaways

- Contrary to the popular assumption that the office of GPS is vested with boundless absolute power, the Directive has endowed no substantive power to it. The GPS has no veto power and no casting vote on any nationwide cross-sector policy issues discussed at any decision-making body at the Party Centre. Instead, the power to make such polices is divided between the CC, the Politburo and the PSC.

- Decisions to impose severe disciplinary sanctions against a member of the CC also have to be made collectively.

- The above is, however, not meant to suggest that the GPS is powerless. As we can see from the table, the GPS has the exclusive power to call for a Politburo or PSC meeting. This power is potentially very valuable because the time and duration of these meetings are subject to no hard constraints, which leaves wide discretion in the hands of the meeting convener. By manipulating such discretion, the GPS can single-handedly stall or delay a decision from being made if strong opposition is anticipated before a meeting or experienced during a meeting. The GPS also has the exclusive agenda-setting power for the Politburo, PSC and the Central Secretariat. Therefore, even though having only one equal vote among quite a few, the Convener/Chair has much greater influence upon the outcome of the decision-making process than any of his peers has.

- The Central Secretariat, which is responsible for policy implementation, answers to the Politburo, the PSC and the GPS. In theory, the Politburo and the PSC can only command the Central Secretariat in a collective consenting voice, which sets significant constraint upon their capacity of exercising this power. However, the GPS is free from such constraint because it is an individual office.

People sometimes tend to (over)emphasize the pattern-breaking and paradigm-changing features that have distinguished Xi Jinping’s administration. This is understandable because, after all, one has to make the unit of comparison small enough to tell with accuracy what is rule-breaking and what in fact shows continuity, and such work is tedious. In this context, it is important to stress here that most of the arrangements mentioned above were already set in the Party Charter in 1982 and have been observed ever since. Some can be traced back even to earlier times. Therefore, these arrangements of and by themselves shall NOT be read as signs of further concentration of power by Xi Jinping.

However, what appears new in the Directive is the formal conferment of the power to direct the operation of the central policy deliberation and coordination bodies (most known as central small leading groups) to the GPS. This power has never been formally bestowed to the GPS in published Party rules before. Also new is the term of agenda setting. Previously, agenda setting is not singled out as a specific mandate of a particular office. Even though, I suspect it had been acquiesced as a derivative of the convening power in practices.